The jaws of life

A local MedTech startup has innovative new designs in the oral and maxillofacial surgery sector.

At the head office of MAXONIQ at the University of Melbourne, there are about 10 devices that could potentially change the lives of people impacted by oral and maxillofacial diseases and deformities. Designed by a team of biomedical engineers and MAXONIQ founder, Dr George Dimitroulis, those devices include a mouthguard that contains sensors to accurately assess bruxism or teeth clenching and grinding, and magnetic dentures.

Dr George Dimitroulis.

But the MAXONIQ journey began with a device that is now being sold internationally – a 3D-printed titanium jaw joint now in its fourth iteration. The implant is used specifically to replace the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), most often as a consequence of osteoarthritis, tumours or trauma.

“At the time there were only two prosthetic devices on the market – one was a custom prosthesis that required initial surgery and the patient’s jaw being wired together for 10 weeks, followed by further surgery to implant the prosthesis. The second option was an off-the-shelf prosthesis that had to be adapted to fit,” explains Dr Dimitroulis.

“I wanted to improve the design and make the procedure safer and quicker.”

With expertise from the University of Melbourne’s biomedical engineering department headed by Professor Peter Lee and Associate Professor David Ackland, the MAXONIQ TMJ prosthesis, or Arthrojaw, was developed. It uses 3D-printing technology and digital planning to create a bespoke prosthesis that costs no more than a standard off-the-shelf TMJ prosthesis.

The device is now being sold in Australia, Mexico and Malaysia with discussions under way in Taiwan, Indonesia and Japan.

Dr Dimitroulis and his team of engineers have also developed the titanium OsseoFrame that is used in patients who need dental implants but who don’t have the bone required to anchor conventional implants.

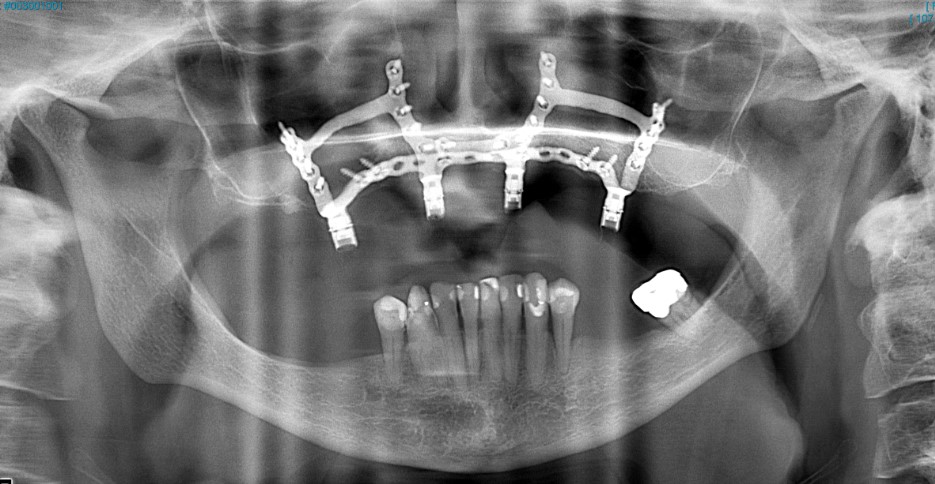

An x-ray image showing the Osseoframe implanted in a patient's top jaw.

“OsseoFrame is a 21st century version of a subperiosteal frame, an idea first conceived in the 1940s. Previously they took an impression of the bone, made a frame in wax and fired it in metal alloys. They then opened the gum a second time and stitched the frame on the jaw bone. It was a two-stage surgery. By the 1960s, this was superseded by screw-in implants,” says Dr Dimitroulis.

“The OsseoFrame is 3D-printed to sit on top of the jawbone, not in it, and it is most suited to patients with no bone for conventional dental implants. It takes less than an hour of surgery to put the frame on the jaw and the patient’s prosthetic teeth are fitted at the same time. It is a revolutionary approach that eliminates the need for any bone grafting.”

Continuing to push boundaries for oral and maxillofacial treatment, Dr Dimitroulis and his colleagues have developed the TriFix custom plating system for patients living with dentofacial deformities, such as a crooked jaw.

“We use computer technology based on CT scans to accurately position the jaws within a millimetre, using patient specific and custom designed bone plates and screws to fit on to the maxilla or mandibular bone below the gum,” says Dr Dimitroulis.

MAXONIQ is working with dental and biomedical engineering school colleagues to develop a mouthguard with sensors to accurately assess bruxism and is investigating the design of magnetic dentures with the University of Queensland.

“Similar to the OsseoFrame, we are developing devices for people who’ve had cancer and are missing a nose, ear or eye so a prosthesis can be fixed directly to bone. We’ve developed 3D-printed titanium frames that are surgically implanted and fix directly to the bone. They incorporate tiny magnets that come through the skin and can be used to attach an artificial ear, nose or eye,” says Dr Dimitroulis.

“In the next 12 months we want to raise money so we can seek FDA approvals in America – the US is 50 percent of the world’s medical device market. With some further research money, we’d like to be able to get some of these devices out of the drawer and in to the patients who need them.”