3D Models and Printing in Dentistry

Dr Hardiman describes Sketchfab as the “social media for virtual model enthusiasts”.

Certainly, it has the same level of shareability and accessibility that Instagram has. You’re also able to reach a wide audience the same way you would on social media sites, which is useful, Rita believes, because “you never know who the model will help in the big world outside the University”. Her models are viewed by school students, researchers, archaeologists and dental professionals alike.

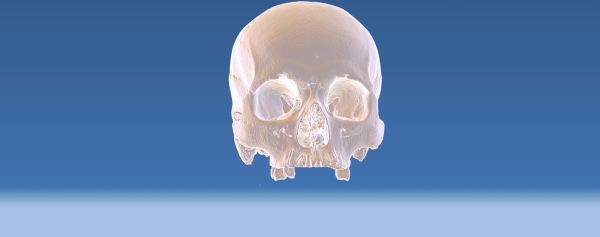

For Hardiman, a love of anatomical collections collided with an ability to scan skulls and teeth from such collections and create 3D models and prints.

“I loved the fact that I could scan a skull using CT, and then use software to shave away parts of the bones virtually to reveal how the teeth are embedded in the jaws.”

The virtual models on displayed on her Sketchfab account transpired from a grant Hardiman and her colleagues secured which gave them access to skulls and teeth from different scientific collections within the University of Melbourne.

How long is the process to create these virtual models?

Hardiman, who has been to Belgium to learn how to use a Bruker scanner, notes that for a microCT scanner, it can take hours to scan skulls and teeth that are on the larger end. A marsupial mouse skull once took six hours to scan. Anything larger than that requires a CT scanner.

Getting one’s hands on suitable skulls can have its difficulties, but technological challenges exist also: scan files are large and storage capacity sometimes lacks the ability to handle all of the data.

“This has changed for the better significantly over the last decade”, notes Dr Hardiman. She thinks it’s possible this had something to do with the increase in gaming technology and requirements.

How will 3D science look like in the next few decades?

Right now, the ability to scan and recreate structures virtually supports our real-life world in many ways. Most notably, a lot of things that in the past could only be done once on a skull—cutting it in half to see the inside, for example—are now possible in infinite ways without destroying the original. Being able to do this repeatedly allows us to do lots of measurements and calculations using virtual scans. This has the benefit of increasing sample sizes for researchers.

And yet, it is possible, Hardiman thinks, that we could find uses for physically bringing into creation things that are visualised in a virtual platform. Teeth are a good example.

“If you think about the way your body makes teeth, it’s already like additive manufacturing.”

At the end of the day, Rita believes that all we have to do is “let this [type of] technology keep capturing our imaginations”.